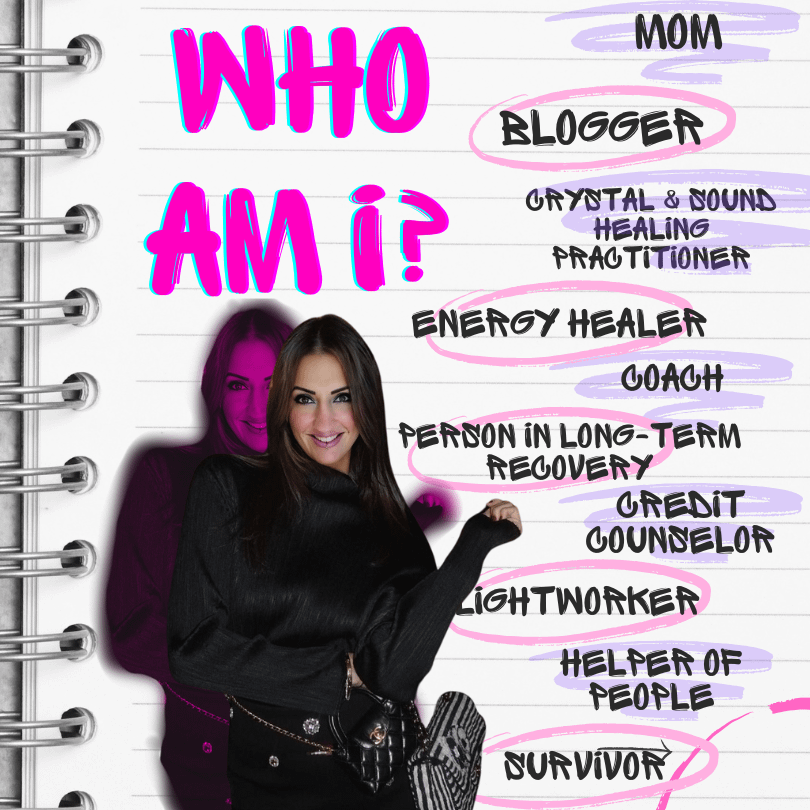

Introduction

I didn’t choose to become a low-level female drug dealer in East Nowheresville, Red Neck, America. I mean- who would? It was forced on me. After my place got raided for the first time, the “justice system” ensured that I wouldn’t find gainful employment for a very long time to come, and what else can you do when NOWHERE hires you, and you don’t even blame them, but I’ll get to that.

I wasn’t just selling drugs—I was selling my soul piece by piece, hiding behind an emotional armor so thick that even I couldn’t break through it if I had wanted to. I built that armor to survive my pathetic existence stuck in near lifelong cycle of addiction, rejection, desperation, and incarceration because, in my world, showing vulnerability was a death sentence, and I avoided it at all costs.

For over 20 years, I played the part. I was fearless on the streets, navigating a world where trust was a liability and weakness a luxury I couldn’t afford. My two best friends, both the biggest dealers in our area, ↗️↗️↗️↗️↗️

inadvertently taught me that survival meant being harder, smarter, and more ruthless than anyone else. I had the smarter nailed, and it wasn’t long before I nailed the part as a whole.

What no one, including my besties, saw was the emotional wreckage happening underneath—the shame, the guilt, the fear that swallowed me whole every single day. No one told me that the same armor that kept me alive would also keep me trapped.

There comes a time when the toughness isn’t enough. One of those many times for me was when the guy I was seeing suffered a fatal overdose, and my best friend went to jail for selling him the dope that he od’d on, except he didn’t.

Suddenly I was watching the Superbowl by myself, looking at the two empty seats beside me. I couldn’t hide behind it anymore. The life I was living—the life that had landed me in jail more times than I could count—had to end.

Cut to me today, with my armor shed and eight years of sobriety behind me, I’m here to tell the truth: being tough nearly destroyed me, but vulnerability saved me. And I’m here to help others take off their armor, too.

I spent so long yearning for freedom that I feel gratitude for every single second. I will never forget what it feels like to have your rights as a human being taken from you.

The powerlessness, helplessness, and hopelessness is something I can’t begin to articulate. I hope and pray you will NEVER know this feeling, EVER. I wouldn’t wish it on the worst human being. I hope sharing my story may be enough to prevent someone from going through what I have gone through.

This is part of my story, but it could be part of anyone’s story—a story of how being forced to be tough can harden you but how breaking free is where true strength lies. ↙️↙️↙️↙️↙️

The Reality of Being a Female Drug Dealer

I want to say that I am in no way proud of my status as a dealer or the fact that I spent my life selling drugs and ruining lives. There is NOTHING to be proud of here, and I am sharing it to heal and raise awareness.

When people picture a drug dealer, they often think of a cold, ruthless figure, someone heartless enough to destroy lives without a second thought. They think of the most infamous, large, and in charge like Pablo Escobar or Griselda Blanco.

↗️↗️↗️↗️↗️

But that’s far from the reality I lived. For me—and for many women like me—selling drugs wasn’t about power or greed. It was about survival. I wasn’t out to be the biggest, baddest dealer on the block. I never wanted to sell drugs. I just didn’t want to feel, at first, and after I just didn’t want to be sick. I was just trying to make it through another day, another week, in a life that felt impossible to escape.

Being a woman in this world comes with a unique set of challenges. On one hand, there’s the constant pressure to prove that you’re just as tough, just as capable as the men. I knew I had to fight harder just to be seen as an equal. On the other hand, society’s judgment hit me even harder because I was a woman, and a woman addicted to heroin before addiction was considered to be a disease medically. It was a nightmare. ↙️↙️↙️↙️↙️

The world sees men in the drug game differently—they’re tough, they’re hustlers. But when you’re a woman, you’re labeled as damaged, reckless, or worse. There’s this stigma attached as if you should have known better as if you should’ve found another way.

But the truth is, I didn’t have another way. I was stuck in a cycle —addiction, incarceration, and the desire to survive and live my best survival. The streets don’t care if you’re a man or a woman. They don’t care about your backstory. You either learn to adapt, or you don’t make it. And for a long time, I learned to adapt. Not making it was not an option.

I learned that in a world dominated by men, a female drug dealer has to be tougher than the toughest guy in the room, or at the very least, you must be able to make everyone else think that you are either physically or mentally tougher.

I got really good at making people think I was things I was not, like confident, for one. I am still not confident, but people often read me as confident. It was initially challenging, but I knew I couldn’t afford to show fear. You can’t afford to be soft. It might have looked like I was in control from the outside. But inside, I was barely hanging on. I became an expert at looking the part, and on the streets, I really didn’t have fear.

To experience fear, I would have had to care about myself and my well-being, and until I had my children, I didn’t at all. I am naturally loud, opinionated, and, when necessary, brutally honest, but I was a good person even when I couldn’t show it. I tried. I always tried.

I had to numb myself to the reality of what I was doing—to the people I was hurting by selling drugs, feeding habits, and making it look fun and trendy. Misery loves company, man. That’s all I got. There is no substantial excuse, and believe I am harder on myself than anyone else ever could be.

In a world where trust is dangerous and vulnerability can get you hurt or worse, I did what I had to do: I armored up. When I got careless, just like the guys, I got locked up, sometimes for my crimes and sometimes for the crimes of others. The few things I had in the world- that I prided myself on was my loyalty to the game, my word, and the fact that I did my own time. I wasn’t giving up nothing to take the focus off myself. I always did the time, even when it wasn’t my time to do.

Not even when I was arrested six months into my pregnancy for my daughter and charged with sales and conspiracy to deliver heroin. It took them twenty years to get a sale on me, and it wasn’t even my sale. It was my baby’s father’s sale.

I was across the street waiting because I had hired him five months prior, and we started seeing one another a little over a month before the sale occurred. I hired him to move my dope. It was technically mine and I needed someone to take my baby after she was born so I did the time.

They wanted me to roll on one of my best friends for his alleged sale with death resulting for the guy I was seeing that OD’d eighteen months prior. Six months pregnant with my first child, seven months sober, and it wasn’t happening. I told them I would take the sale of heroin if they dropped the conspiracy and if they didn’t send my kid’s father to jail.

I would do the time, but he had to be out to care for my daughter once she was born. He ended up cheating on me while I was locked up for his sale, keeping him out of jail and being six months pregnant with his daughter. The first time I ever knew that mental pain and anguish could be felt physically in your heart. Even still, Omerta.

In that life, there’s no time to process emotions or reflect on the morality of your actions. Every day on the streets is about making it to the next one. It’s about survival, staying well, and staying out of jail the best you can, plain and simple.

Building the Armor

I quickly realized that survival meant more than just staying alive—it meant shutting off parts of myself that made me human. The streets demanded a version of me that was cold, calculating, and, most of all, untouchable. This wasn’t me. I’m an empath who cares about people and would do anything for someone in need.

Not to mention, I genuinely care about being a good person despite my many bad habits. That’s where the emotional armor came in. I didn’t just build it; I crafted it carefully, piece by piece, each layer protecting me from the world I was living in. I had to, or all of the pain caused would be more of my own.

The first layer of my armor was control. I learned early on that emotions were a liability. Fear, sadness, guilt—those feelings would only slow me down or get me hurt. So I pushed them down, way down, and became a master at controlling my emotions.

On the outside, I was stoic, unbothered. I had to be. In that world, showing weakness meant people would test you, come after you, rob you, try to break you, and I couldn’t afford that. Not when I was trying to survive in a game dominated by men and violence.

The next layer was detachment. I learned how to distance myself from the people around me—friends, family, and even my two best friends. I had to detach from myself, too, from the choices I was making. I wasn’t just selling drugs; I was selling pieces of myself. But if I allowed myself to feel that, to think about the lives I was affecting, I wouldn’t have been able to continue. So I didn’t think about it. I somehow managed to turn off my empathy outwardly, but inwardly, the more dope I sold, the more I detested myself. Detachment became my new normal.

Then came the constant state of hypervigilance. In the world of drugs, trust is a rare commodity. You can’t trust anyone, not fully, and I was never good at this because I have a tendency to see the good in people no matter how much bad is there.

You’re always waiting for the other shoe to drop, for someone to betray you. I was always on guard, always watching my back, and always anticipating the worst because, more times than not, I let my guard down. I didn’t realize it at the time, but that level of hypervigilance was exhausting.

It consumed me. I couldn’t relax even if I wanted to. Even when things were “good,” I was waiting for the moment when everything would go wrong, and they always did. The fear of going to jail and losing EVERYTHING yet again was never far from my mind. I did time for more than twenty years, and fifteen of them I spent swearing I would rather die than go back. You wouldn’t believe my resilience if I told you. I don’t know how I did it.

Finally, the hardest layer to build—and the hardest to break—was the cold decision-making. I acclimated to making choices that I didn’t want to make without emotion. It was necessary. I had to treat the business like a business. Whether it was risking my life for a deal, cutting ties with someone I’d known for years, watching people I cared about spiral deeper into addiction, or getting dragged into a dark alley by two men in Troy who weren’t interested in drugs or money.

I couldn’t let myself feel anything. In the drug world, making decisions based on emotions was dangerous. So, I shut that part of me off, too. Everything was about survival, even when survival meant making decisions that hurt others and, eventually, myself.

I still freaked out when my neighbor tried selling me her food stamps, knowing she had five kids that needed to eat all month. She went elsewhere and succeeded, and I ended up feeding those kids all month, and I couldn’t let anyone know.

She came to me when they were infested with headlice, and while in CT that day, I purchased eight boxes of shampoo, a couple of combs, some spray, clothing detergent, etc. I paid a friend to drop it all off, never to mention that it was from me. I internally called myself a closet contributor, and I contributed a lot. It was my self-imposed penance, but it made me feel a little better. Helping the right people usually does, but it can also hurt too.

At the time, I didn’t realize that each piece of this emotional armor wasn’t just protecting me from the outside world—it was trapping me inside. I thought I was building something strong, something that would keep me safe. But the truth was, the more layers I added, the more disconnected I became from who I really was. I wasn’t just hiding from the dangers of the drug game; I was hiding from myself, from the pain and the guilt that I didn’t want to face.

Looking back, I see that the armor I built was both my greatest defense and my biggest downfall. It kept me alive, yes. But it also kept me from living, from feeling, from being anything other than the version of myself I thought I needed to be to survive. And it wasn’t until years later, after hitting rock bottom, that I began the painful process of breaking it all down.

Now, we are just getting started. Later on, things became much more difficult. Let’s talk about the people that I injected with heroin for the first time who are no longer with us because they overdosed and died—at least one of them right before my eyes. I won’t tell you what this does to you, but I am sure you can imagine.

Everyone thought I would be one of the ones to have a fatal overdose, but somehow here I am. I have lost everyone I care about to overdose. I stopped counting at fifty-three, and there were so many more.

Living with the emotional weight led to years of depression, anxiety, and PTSD. I carry the trauma of the life I lived with me every day. It didn’t matter how tough I looked on the outside—the emotional scars ran deep and still do.

The cost of being tough, of being a female drug dealer, wasn’t just about the legal consequences or the physical dangers. It was about the emotional wreckage I left in my own life. It was about losing people I loved and losing touch with who I really was, hiding behind an identity I thought I needed to survive. While that toughness kept me alive for a time, it also nearly destroyed me, and in the end, it was completely unnecessary because none of it even matters now, and it never did. I was just too high and dumb to know it.

The Cost of Being Tough

I was constantly surrounded by people who needed me and wanted me around—friends, business associates, customers. It didn’t take long for me to get addicted to that feeling, even though I knew exactly why they wanted me around. Not to mention that I could buy anything I wanted just for fun or entertainment.

This was one of the reasons I began trafficking into the jail. I needed to be needed, and this need would eventually lead to me spending a lifetime inadvertently

If there was something I didn’t want to do, I was kicking someone a little to bring all of our clothes to the laundry mat and do our laundry, even if they didn’t have a car.

This is the stuff that keeps me up at night. I exploited their addictions to get my housework done. Like, who does that? It’s a double edge sword for me because I was doing this, but on the fly, I was helping people and more times than not, I got seriously screwed over again and again. I called it ‘hurt for helping,’ and it sucked. It still happens.

But the toughest part of it all was the emotional toll it took on me. The armor that once protected me eventually weakened. I couldn’t escape the guilt and shame that came with being a dealer. I knew deep down that what I was doing was wrong, but in those twenty years, I would be released from jail more than a hundred times, and every single time, I had the best intentions, and I would hit the ground running, but I always ran out of steam more and more with each repeated rejection.

Every time, I applied to the same places that had been throwing out my applications as soon as I walked out the door. I tried. I tried so hard. Nobody would hire me. Nobody would give me a chance. Surprisingly, I have a great resume.

Before the raid at my house, I had managed a snowboard shop for three years and been a nursing assistant for almost four years, but making the first page of the paper consistently over the years with my name was, for some reason, people always remembered, apparently something that stuck. Two or three places laughed at me when I tried to drop off my resume.

“Noooo. Uh-huh! Don’t waste your resume here. Not happening.” It was so humbling, and it hurt, but I had no one to blame but myself.

Breaking Down The Armor

For me, the turning point came when I found out I was pregnant. Up until that moment, I had lived my life for myself and satisfying my needs—moving from one risky situation to the next, hiding behind it all, and convincing myself that I didn’t need anyone or anything. But knowing I was going to become a mother changed everything. Suddenly, it wasn’t just about me anymore. I couldn’t keep living that life, trapped behind the walls I had built. I had to find a way out—for myself and my baby.

It wasn’t an easy journey. Letting go of the armor I had built for my role as a female drug dealer meant facing all the emotions I had buried for so long. The guilt, the shame, the fear—they all came rushing back as soon as the numbest that dope allowed me for so long began to fade. For the first time in years, I had to confront the reality of what I had done, the people I had hurt, and the life I had lived. And that was terrifying. But it was also necessary. If I didn’t break down that armor, I knew I would never be able to truly heal.

The process of recovery didn’t happen overnight. I walked into a homeless shelter with a 450 credit score and a correctional GPS monitor around my ankle, ready to start over. That was eight years ago, and I’ve been sober ever since. But getting sober wasn’t just about giving up drugs—it was about giving up the people and the life but, more importantly, giving up the emotional armor that had kept me alive in the drug world but was now holding me back from living a real, meaningful life.

Breaking down that armor meant learning to feel again. I had to reconnect with my vulnerability, with the parts of myself that I had hidden for so long. I had to learn how to ask for help, how to trust people again, and most importantly, how to forgive myself for the choices I made as a drug dealer. Forgiving myself was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done, but it was also the most important step in my recovery. I had to accept that while I couldn’t change the past, I could choose how I moved forward.

In breaking down my armor, I discovered a strength I never knew I had. For so long, I thought being tough meant never showing weakness, never letting anyone in. But in reality, true strength comes from vulnerability. It comes from being able to face your mistakes, own them, and use them as a way to grow. Vulnerability is so much more difficult.

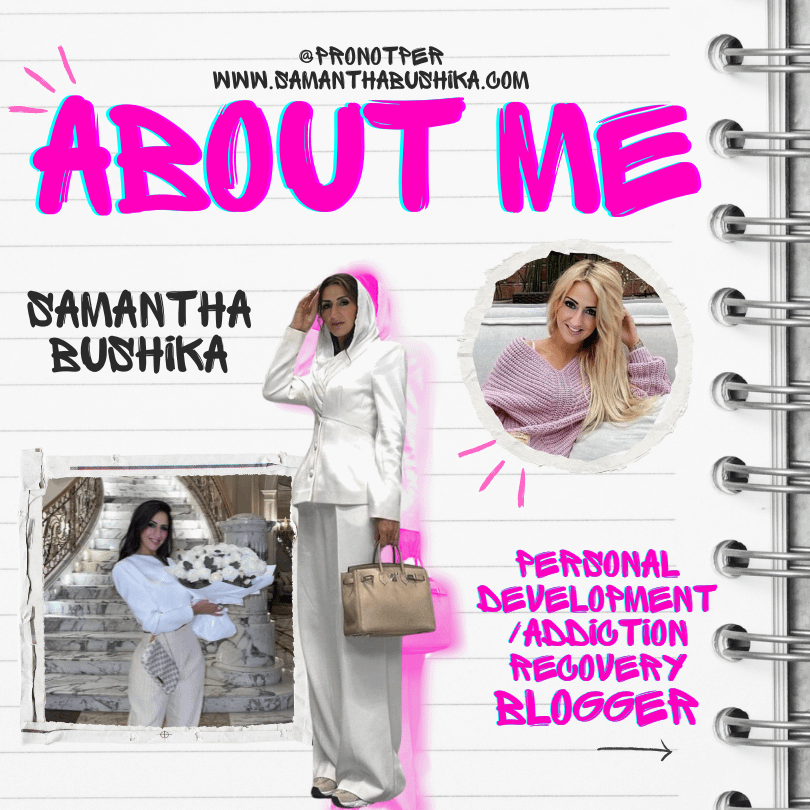

Now, with eight years of sobriety behind me, I’ve dedicated my life to helping others break down their own emotional armor. I became a Certified Addiction Recovery & Life Coach because I know how isolating and painful it can be to live behind that toughness, especially as a female drug dealer. I got into Reiki because everything is energy, and for me, aligning my Chakras changed everything. I could breathe again, and without illicit drugs, which I never believed to be possible.

I want to show other women—and anyone else struggling with addiction, incarceration, reintegration, mental health, or anything that makes life harder —that there’s a way out. You don’t have to keep hiding behind your armor. You can break it down. You can heal. And you can rebuild your life, just like I did. One of the main things that has kept me on the path is those I’ve lost. I am determined to make it count for them. There is a reason I am one of the last ladies standing. I have to make it count for them.

Lessons

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from my time as a female drug dealer and my journey through recovery, it’s that the emotional armor we build to protect ourselves can become our greatest enemy. We think it’s keeping us safe, helping us survive, but in reality, it’s keeping us trapped in a cycle of pain, isolation, and fear. I’m not the only one who has lived this story. Many women in the drug world, and in addiction in general, have had to become tough to survive. But the real challenge comes when it’s time to let that toughness go and reclaim who you really are.

We think it’s keeping us safe, helping us survive, but in reality, it’s keeping us trapped in a cycle of pain, isolation, and fear. I’m not the only one who has lived this story. Many women in the drug world, and in addiction in general, have had to become tough to survive. But the real challenge comes when it’s time to let that toughness go and reclaim who you really are. ↙️↙️↙️↙️↙️

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned is that empathy is key—not just for others, but for yourself. I stuffed empathy so deep. I couldn’t afford it. I had to try to stay detached to keep going. But now, looking back, I see how essential it is to break that cycle. If you know someone who seems tough, hard, or unreachable —Especially a woman who has lived through trauma or addiction—try to look beyond the surface. Understand that this emotional armor was built out of necessity. No one chooses to be that way; they become that way to survive. Offering understanding, compassion, and a safe space to heal can make all the difference.

Society often paints us as ruthless, selfish, or beyond help. One of the reasons the criminal justice system didn’t think I was worth rehab. But the truth is, most of us got into the drug world not because we wanted to but because we felt like we had no other choice. We need to start seeing these women, these people, for who they really are—humans, struggling with deep pain, often trapped in circumstances they don’t know how to escape.

Reclaiming vulnerability has been the most powerful part of my recovery. For so long, I thought vulnerability was weakness. I thought being impenetrable was the only way to get by. But real strength comes from being able to face your emotions, to feel deeply, and to allow yourself to heal. It’s about being honest with yourself and others, even when it hurts. That’s something I try to teach the people I work with now as a coach—your vulnerability is not a weakness; it’s your power. It’s the key to your healing.

For anyone reading this who feels like they’ve had to wear emotional armor, whether as a female drug dealer, in addiction or just from life’s challenges, I want you to know that it’s okay to start letting that armor fall away. It’s okay to feel, to cry, to be vulnerable.

Healing begins when you allow yourself to be human again. You don’t have to stay tough forever. There is a way out, and it starts with taking off the mask you’ve been hiding behind for so long.

I’ve lived the life. I’ve worn the armor. I’ve survived the streets, experienced the consequences, and done my time. But the greatest victory of my life wasn’t in surviving it all —it was in breaking down that armor and learning how to live authentically again. You can do the same. It’s never too late to heal, to grow, and to find your true strength in vulnerability. I have a four-year-old son and a seven-year-old daughter. I had my first child at the age of thirty-six. It is NEVER too late. Change your mindset, change your life. You deserve so much more.

Conclusion

Unlike Griselda Blanco, the so-called Godmother of Cocaine, or the notorious Pablo Escobar, my story isn’t one of a vast empire built from tons of cocaine. I wasn’t some infamous drug lord with a lavish lifestyle flaunting wealth and power. I wasn’t a crime boss orchestrating deals in New York City or operating a criminal activity syndicate under the cover of broad daylight. My life story is much simpler and much more painful. I sold drugs to fuel my addiction, not to live in luxury, and I was far from proud of it. I wasn’t a central figure among drug traffickers or drug charges—I was just trying to survive and be functional while doing so.

I didn’t have the resources or power of the infamous drug traffickers who moved kilos of cocaine across the United States in the early 1980s. I was more like countless other non-violent, addicted, broken, not worthy of treatment, convicted felons that the world had shut out, struggling to keep my head above water, trying to find a way out of the mess I was in. But no matter how much I distanced myself from that criminal persona, the shame clung to me. The emotional armor I built wasn’t to protect a lavish lifestyle—it was to hide my pain, my addiction, and my fear of being judged by the criminal justice system and society.

I share my story not because I want to glamorize the life I lived but because I want to show others that it’s possible to escape it. You don’t have to be a Griselda Blanco or a Pablo Escobar to feel trapped by the weight of your past. Whether you are dealing drugs or facing other battles, we all wear emotional armor to protect ourselves. But that armor, as strong as it seems, only keeps us locked in. Taking it off is terrifying but also the most freeing thing you can do.

I wasn’t a godmother of cocaine or a crime boss; I was a woman caught in a cycle of addiction, incarceration, and survival. I sold drugs, yes, but only to support my habit, and I’ve spent years working to heal from that life. My hope is that my life story can help others, those with addiction, anyone who feels like they’ve been judged for their past—find the courage to take off their armor and start living again. We don’t need to be defined by our past, our mistakes, or the criminal personas we were forced to adopt. We can break free, find healing, and build new lives we can be proud of.

I did it. And if you’re reading this, you can too.

For years, I believed that being tough was my only option. I thought my emotional armor was my greatest weapon, my shield against a world that seemed determined to break me. But now, after eight years of sobriety, I understand that the armor I built wasn’t just keeping others out—it was keeping me trapped. It kept me from feeling, from healing, and from truly living.

The toughest battle I ever fought wasn’t in the streets or against the system—it was against myself. It was the battle to take off that armor and allow myself to be vulnerable again. In doing so, I discovered that real strength doesn’t come from being invincible; it comes from being willing to face your pain, your mistakes, and your truth head-on.

To anyone reading this who feels like they’ve had to be tough to survive, who’s been wearing their emotional armor for so long that they’ve forgotten what it feels like to be vulnerable—I see you. I know how heavy that armor is, and I know how terrifying it can be to even think about taking it off. But I promise you, on the other side of that fear is freedom. On the other side is healing. On the other hand, there is the chance to rebuild your life in ways you never thought possible.

Being a female drug dealer was a large chapter in my life, but it doesn’t define me. What defines me is how I’ve chosen to rise from that life, reclaim my vulnerability, and use my story to help others find their own strength. If I can shed my armor after years of believing it was the only thing keeping me safe, so can you. It’s never too late to start over. It’s never too late to find your real strength.

The armor may have protected you in the past, but you don’t need it anymore. Let it go. You deserve to be free.

If This Post...

If this post resonated with you or you have something you would like to add or share, please do so in the comments below. You know I love to hear from you.

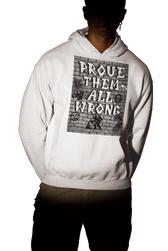

You could also support my work by liking, sharing, commenting, subscribing, following, and registering to join our free-of-charge, supportive, all-inclusive, judgment-free, meet-you-where-your-at online community where teachers learn, and learners teach all while working together to #provethemallwrong and #showthemwhatwecando.

In our support forums, you can give support or receive support all on the same day. This community is for all of us who are more progressors, less perfectors. Addiction is not a prerequisite. All are welcome. This is a new, growing community, so please have patience, and if there are any issues, please contact me at [email protected].

Post Off Quote

"If you can't fly then run, if you can't run then walk, if you can't walk then crawl, but whatever you do you have to keep moving forward."

-Martin Luther King Jr.

Post Off Affirmation

I am allowing strength, support, blessings, and my ability to make the right choices into my life for good.

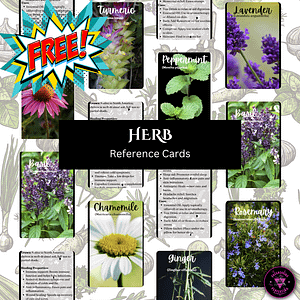

Check Out|Related Posts|Below

Click on the post above to check out the post.

More From This Category

Why Lightworkers Struggle with Addiction: 7 Hidden Reasons (And How Shadow Work Can Help)

[dsm_text_divider header="%22I thought being a Lightworker meant I was supposed to have my shit together.%22"...

The Law of Attraction Experiment That Ended My Addiction: A Raw Manifestation Success Story

[dsm_perspective_image src="https://www.samanthabushika.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/1-2-1024x1024.png" alt="The Law of Attraction Experiment That Ended My Addiction: A Raw Manifestation Success Story" title_text="1" _builder_version="4.27.4"...

Overcoming Adversity: How My Lowest Moments Forged My Strongest Self

The Collapse — When Everything Fell Apart There’s something about difficult times that strips you to your bones. Overcoming adversity is never easy, but what is in these times. I remember standing in a difficult situation that no one prepares you for — the kind where...

Why You Can’t Meditate (and What’s Really Going On)

[dsm_perspective_image...

Why Lightworkers Struggle with Addiction: 7 Hidden Reasons (And How Shadow Work Can Help)

[dsm_text_divider header="%22I thought being a Lightworker meant I was supposed to have my shit together.%22"...

0 Comments